What Calculus 1 Actually Teaches You

It's not the formulas. It's learning to reason.

My generation is the first to openly deviate from academic studies. “You don’t need a degree” has become a common saying, almost a badge of honor in tech circles.

Around me in high-tech, many developers are frustrated that they spent 3 years studying mathematics and computer science, only to “never use” what they learned in the industry. They calculate no derivatives. They prove no theorems. The elegant proofs from first-year courses feel like a distant, irrelevant memory.

And yet.

There’s a course in the first semester that haunts every CS and engineering student: Calculus 1. Half the students fail it the first time. Most suffer through it and avoid anything similar for the rest of their lives. Discrete math, linear algebra, logic - these first-year courses share the same reputation. Brutal. Abstract. Seemingly disconnected from the “real” work that comes later.

Could there be a connection between this early struggle and the later feeling that “none of it was useful”?

I believe there is. And I believe most people are measuring the wrong thing.

The Wrong Question

When developers say they “never use” their degree, they’re asking: When did I last calculate an integral? When did I apply set theory directly to my code?

This is like asking when you last used the specific exercises you did in the gym. You don’t use them - you use the strength they built.

The first-year math courses provide foundation for the courses that come next. But the foundation isn’t just the definitions and theorems - it’s also the thinking. These courses are there to rewire your brain. To force you, for the first time in your life, to think mathematically.

What “Thinking Mathematically” Actually Means

Before Calculus 1, most students have only experienced math as pattern-matching. You see a problem type, you recall the formula, you apply it. This works through high school.

Then you hit university math, and suddenly:

Problems don’t announce what technique to use

You need to construct arguments from first principles

Precision of language matters - a slightly wrong definition breaks everything

You must hold abstract structures in your head and manipulate them

This is genuinely hard. Not because the content is complex, but because it requires a different kind of thinking than most people have ever done. Your brain literally needs to form new pathways.

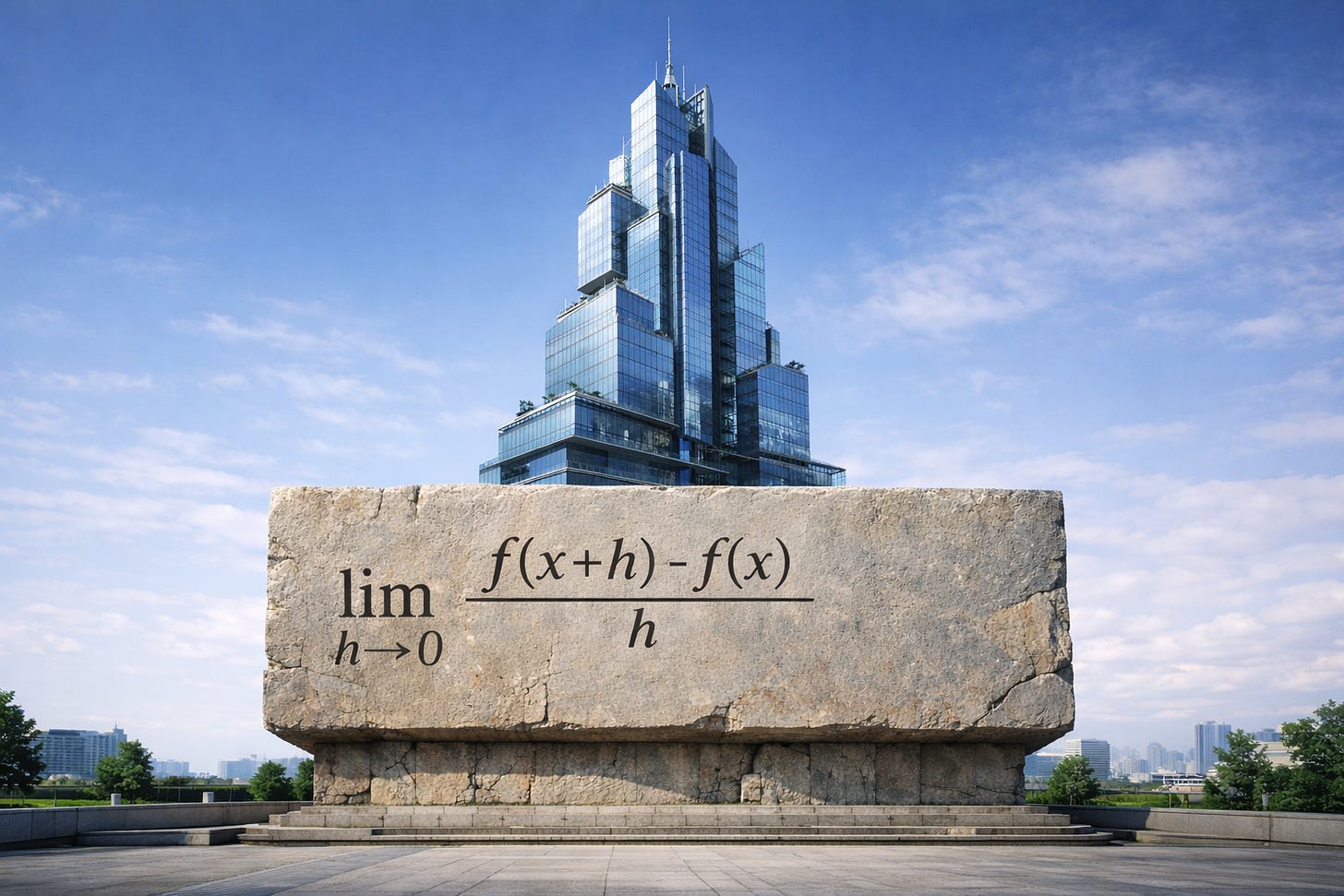

The students who fail Calculus 1 aren’t failing because they’re not smart. They’re failing because they haven’t yet made this cognitive shift. This is the strange binary nature of mathematical understanding: if you don’t get it, you fail completely. If you do get it, you can forget all the material and rebuild it yourself - a student who truly grasps Calculus 1 can reconstruct the entire course from just the definition of the limit. The difference isn’t memory or intelligence. It’s that you’ve learned to reason.

How This Shows Up in Real Work

I consider myself a mathematician more than anything else - not because I do math professionally, but because mathematical thinking shapes how I approach everything.

As a product manager and entrepreneur, I run many experiments. When I test something - a value proposition, a target audience, a piece of creative content - I instinctively fix variables. If I’m testing creative content, I keep the audience constant. This way, the search space is smaller, and feedback is interpretable. This isn’t “using calculus.” But it’s the same thinking: isolate variables, reduce dimensions, make the problem tractable.

When I develop a system, I mentally map its possible states and behaviors. If something breaks, this map tells me exactly where the bug could live. I’m not running through code line by line - I’m reasoning about the system’s structure. Again, no integrals involved. But the thinking is mathematical.

The Observable Difference

Over the years, I’ve watched many people work through technical problems - some with strong math backgrounds, some without.

The pattern I see: people without mathematical training tend toward pattern-matching conclusions. They see something that looks similar to a past problem and jump to a solution. When they’re wrong, they’re often way off - not close, but in a completely different territory.

People with mathematical training tend to break problems into pieces first. They generate observations before conclusions. They ask “what type of problem is this?” before “what’s the answer?” When they’re wrong, they’re usually wrong in a more contained way - they can identify which piece of their reasoning failed.

This isn’t about intelligence. It’s about trained habits of thought.

The Counterargument

“But plenty of successful developers never went to university.”

True. And when I look closely at these people, I usually find one of three things:

They learned mathematical thinking elsewhere - through competitions, online courses, self-study, or intense curiosity about how things work

They developed it through years of hard experience, essentially putting themselves through the same cognitive training the degree provides, just slower

They’re genuinely exceptional - rare people who think this way naturally

The degree isn’t the only path. But it’s a structured, efficient path. One year of intense mathematical training, guided by people who’ve thought deeply about how to build these skills. You don’t need to commit to a 3-year program - but that first year is worth the investment.

The question isn’t “degree vs. no degree.” The question is: “How will you develop the right tools for combating problems in your future life?” If you have another answer, great. But “I’ll skip it entirely” is not a viable answer for serious technical work.

Why This Matters Even More in the Age of AI

There’s a concern I hear from young people now: “AI can do so much of the technical work. Why do I need to learn this stuff if AI can do it for me?”

This misunderstands what we’re talking about.

AI can generate code. AI can solve equations. AI can even explain concepts. But AI doesn’t think for you. You still decide what to build, how to break down a problem, what questions to ask, whether an answer makes sense.

Mathematical thinking isn’t about doing calculations - it’s about structuring thought. And the person who thinks clearly will use AI far more effectively than the person who doesn’t. They’ll ask better questions. They’ll spot nonsense outputs. They’ll know when to trust the tool and when to doubt it.

If anything, AI amplifies the value of clear thinking. The gap between someone who thinks mathematically and someone who doesn’t will only grow.

What I’d Tell My Younger Self

If I were advising someone starting out today, I’d say: the first year of a math, CS, or physics degree is more valuable than the rest combined.

Not because of what you learn - but because of what it does to your brain.

The later years teach you specific domains. Useful, but replaceable through experience or self-study. The first year teaches you to think. That’s much harder to acquire on your own.

If you’re going to do a degree, take the first-year math courses seriously. Don’t just pass them - actually let them change how you think.

If you’re not going to do a degree, find another way to get this training. Math competitions. Working through a rigorous textbook with proofs. Building things that force you to reason precisely.

But don’t skip it. The “you don’t need a degree” crowd is right that you don’t need the credential. They’re wrong if they think you don’t need the thinking.

Really agree. And I find this very similar in two domains -

1. Studying statistics (theorems, distributions, calculations, tests) and actually doing research (reasoning by yourself which tools are relevant and which aren't and applying them).

2. Studying mental health and therapy books and textbooks (criteria, patterns, behaviors, treatments) and actually becoming a good therapist (learning to distinguish out of everything your ever learnt what matters and what doesn't (and a whole lot of experience, reflection, understanding how the patient thinks and changes, learning to connect with the patient)).

In both cases, you can't achieve the latter without the former, even if you feel the former isn't always relevant.